Harbour Fest Reference

Introduction

An outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) in Hong Kong in early 2003 killed almost 300 people in a few short weeks and left hundreds more with long term medical problems. It also had a severe – but luckily short term – impact on the local economy. A Government campaign to help the community cope with the economic consequences, and then revive the economy, was broadly successful and by the end of the year Hong Kong was steaming ahead in its usual full throttle way.

But one item within that Economic Relaunch programme became a political hot potato. The controversy led to disciplinary action being taken against the head of a small government department though no minister was held politically accountable.

In 2007, the civil servant concerned, having been found guilty by an internal disciplinary panel and having suffered a small penalty, took legal action to clear his name. He sought a Judicial Review in the High Court of three decisions against him, one each by the Chief Executive, the Chief Secretary for Administration and the Secretary for the Civil Service. Moreover the grounds he cited to justify the review were by implication critical of actions and decisions by the Secretary for Justice and the Financial Secretary of the time. In effect therefore he was taking on all five of the most senior political leaders, a royal flush of the Administration so to speak.

Yet not only did the civil servant win the court case (heard in 2008), he kept his job and retired a few months later with honour. And the Judge who ruled in his favour got promoted to the Court of Appeal.

These events would have been remarkable enough in any society at any time. It is difficult to think of another community in Asia or even the world where they would be possible. Yet they took place in Hong Kong 11 years after China resumed the exercise of sovereignty over the one-time British Colony. A tribute both to the Central People’s Government’s respect for Hong Kong’s “high degree of autonomy” as promised in the city’s constitutional document known as the Basic Law, and to the resilience of the institutions left behind by the British and nurtured meanwhile by Hong Kong citizens. The Common Law system remained firmly in place and all remain equal before the law.

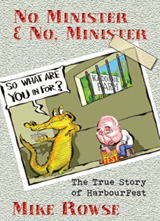

Much has been written about the events which formed the backdrop to the Judicial Review and the disciplinary proceedings which preceded it. But a great deal of the material was inaccurate, or at least incomplete. Hence my decision to write this book. For I was that civil servant, and it is time for the true story – the complete story – of HarbourFest to be told.

I have not written the book with the intention of absolving myself of any blame for the problems that arose, nor to point the finger at others. Rather, I have sought to set out what I did and didn’t do, and why.

More importantly, the case illustrates a significant structural problem that has arisen since the introduction of the system of Ministerial Accountability in 2002. Unless that issue is addressed, there will be more such instances in future hence casting a shadow over the quality of governance in Hong Kong.

Before we begin the story, we should note that while Hong Kong is a major city of some 7 million people, in many ways it seems more like a village. The circle of people holding senior positions in the Government, in political circles, in the professions, in the private sector or even in major social and sporting organisations, is fairly small and there are many overlaps. It would be all too easy to suspect or imply collusion or conspiracy when there is nothing of the sort, only a perfectly innocent coincidence.